Dr Will Jackson Senior Lecturer in Criminology LJMU Centre for the Study of Crime, Criminalisation and Social Exclusion

Playing the Future: PTown Bay MMXXX

Key Points

- PTown Bay MXXX is co-produced artwork that takes the form of a board game which offers new insights into the experiences and future aspirations of disadvantaged young people.

- Drawing on the principles of ‘serious games’, PTown Bay MXXX demonstrates that examining issues of social, climate, and criminal justice through the medium of play is to take them seriously.

- As players, PTown Bay MXXX asks us to think about the ways in which disadvantaged and/or marginalised young people can inform debates about the future of their environment and their community.

- This project further highlights the potential of Criminological Artivism as a new and effective way of engaging audiences with a view to informing campaigns for penal reform as well as social and climate justice.

Introduction

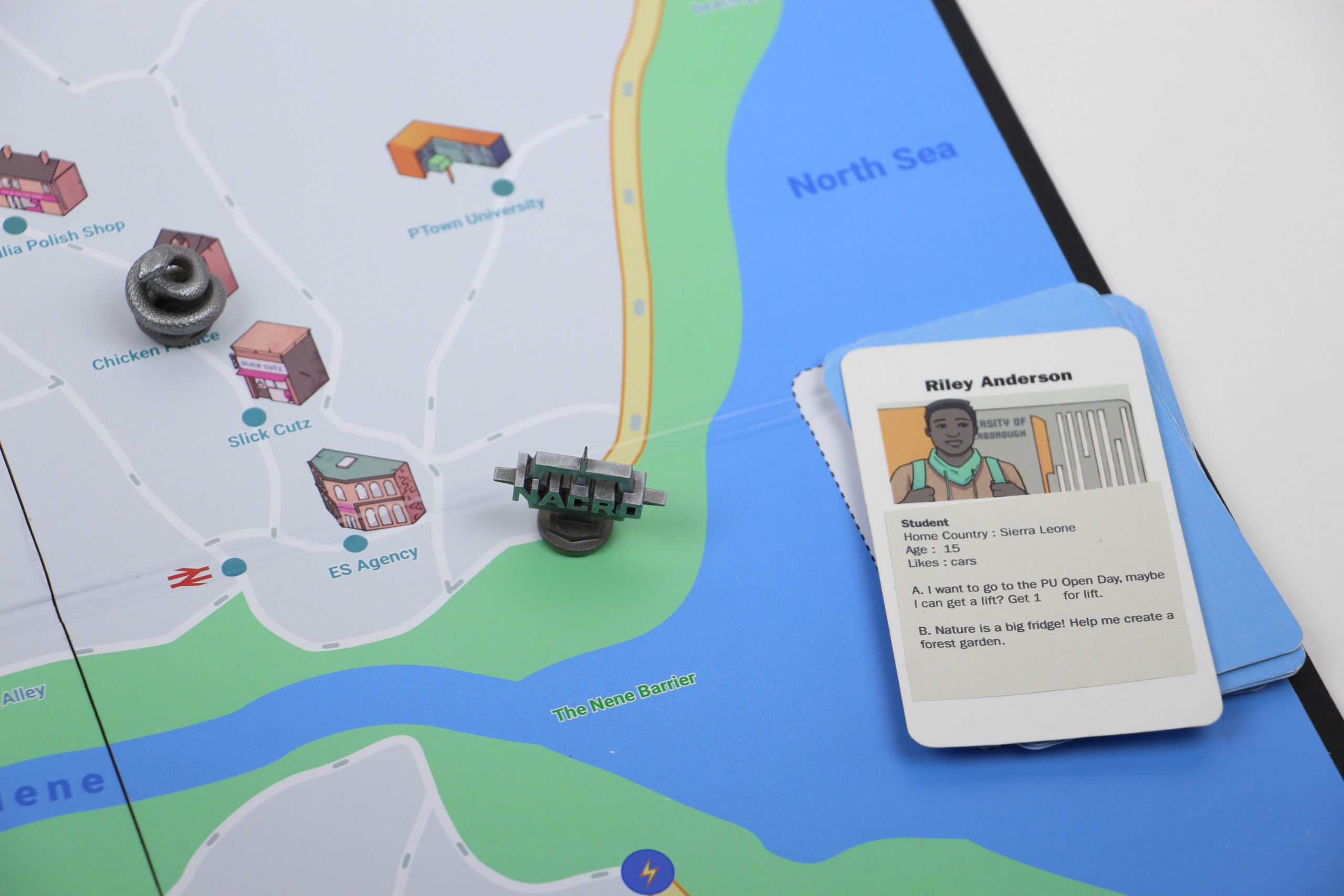

PTown Bay MMXXX is a board game co-created with disadvantaged young people. The game was created through a programme of Socially Engaged Art workshops held under Covid-19 restrictions at the Nacro Education and Skills centre in Peterborough. The game is set in a future world transformed by climate change and provides a unique way of exploring the current and near future aspirations of young people facing multiple disadvantages.

The project was a Season For Change, Common Ground commission led by the artist Hwa Young Jung and supported by a collaboration between Nacro, The Howard League and Liverpool John Moores University [LJMU]. This interdisciplinary collaboration between the fields of art, social justice, penal reform, and criminology sought to inform debates about social, criminal, and climate justice. Specifically, the PTown Bay MMXXX project was designed to engage disadvantaged and marginalised young people with their community, climate change, and the environment.

Background

This project builds upon a partnership between The Howard League and LJMU which focusses on the development of creative methodologies and approaches to the design, delivery, and dissemination of research knowledge and ideas. Bringing criminology, art, and penal reform together, our on-going work seeks to explore how innovative research can inform and underpin campaigns for change. It is our shared view that such an approach allows for a greater emphasis on co-production, working alongside diverse stakeholders, to help generate the research questions to be asked, the methods to be used, and the techniques employed to engage audiences and drive impactful policy change.

Through this collaboration we have sought to examine the potential of Socially Engaged Art [SEA] for criminological inquiry and penal reform campaigning. Encompassing a wide range of methodologies, SEA is a unique art form which ‘involves people and communities in debate, collaboration, or social interaction’ (Tate, 2021). This approach to artistic practice ‘operates within the social context which it considers, rather than simply representing or responding to a subject’ (Murray, Davies and Gee, 2019: 185). In-line with participatory methods in criminological inquiry, SEA also seeks to address power relations, understanding those with lived experience as ‘research partners’ in knowledge production or ‘co-creators’ in artistic production. Utilising SEA as a tool for social research – and for criminological research in particular – this experimental approach invites us to think and work differently as both researchers and campaigners.

This approach led to the development of an aligned model of research practice within which criminological researchers, artists, and penal reform campaigners collaborate in new ways to engage with both participants and audiences as we co-produce and share research. Aligned practice is based on the synergies between creative methods of social research, campaigns for penal reform, and SEA. This interdisciplinary and collaborative approach transforms the way we work with marginalised groups and the way we share research and campaigns with diverse audiences. In this model, researchers, and campaigning organisation work with artists to inform, but not dictate, both the creative process and the focus and form of the artwork that is co-produced by artist and participants. We believe that this approach has the potential to transform how we examine key penal reform and social justice issues, and to change the ways in which we engage audiences with a view to changing policy.

We refer to this approach to aligned practice as Criminological Artivism and it was this model that was applied by The Howard League, the team at LJMU, and Hwa Young Jung, in the production of Probationary: The Game of Life on Licence in 2018. This pilot project sought to explore the potential of SEA as a means of examining the application of the licence system by the probation service in England and Wales. Utilising the medium of play as a mode of dissemination, Probationary enabled us to consider how artwork can change attitudes as part of a campaign to change policy. The reception Probationary received has suggested a wider potential of this mode of collaborative work between academic, artistic, and penal reform sectors (Jackson, Murray and Hayes, 2020).

Aligned working under public health restrictions

The PTown Bay MMXXX project sought to develop Criminological Artivism and to explore how aligned practice could be undertaken when collaboration in-person is not possible. In previous pilot projects, collaboration between researchers, artists, and campaigners has been done in shared physical spaces. Co-production of both digital and analogue artworks has been grounded in interactive, creative, in-person workshops. These SEA workshop sessions have emphasised collaboration, negotiation, and consensus building to produce artworks that represent the experiences of those involved in its creation.

The Covid 19 pandemic and resulting restrictions required us to rethink the approach to co-production and aligned practice. Beginning in early 2021, with the UK under its third national lockdown, the programme of workshops at the Nacro Education and Skills Centre in Peterborough were led by Hwa Young Jung virtually and facilitated in-person by artists Prin Marshall in 2021 and Hana Sayeed in 2022 alongside Nacro staff. Video conferencing enabled Hwa Young to engage with participants and enabled a regular dialogue with the research and campaign team. Anita Dockley, Research Director at The Howard League, and Dr Will Jackson both worked closely in a virtual format with Hwa Young Jung as advisors, engaging with, and informing, the creative process.

The move to a hybrid model of aligned practice brought benefits and challenges that informed our evolving approach to the application and development of creative methodologies. In the first instance, the availability of video conferencing enabled the lead artist in this project to engage with a community without having to be there in person. This enabled us to work within lockdown restrictions and to work in a new community for an extended period without having to navigate the financial and time costs of travel. This suggests a future potential to collaboration in this format without many of the usual limits imposed on research and campaign activities.

The challenges of aligned practice under lockdown conditions lay in engaging young people through extended workshops facilitated by video conferencing. While the availability and accessibility of video communication increased during the pandemic, it can be hard to engage participants for extended periods. ‘Zoom-fatigue’ was managed by the presence of co-facilitators working in the room under the guidance of Hwa Young Jung who remained present via video throughout.

State of play

This project also sought to examine how the format of ‘serious games’ could be utilised to examine the experiences of young people not in mainstream education. The practice of using games for political and pedagogic purposes is not new (Mayer and Bekebrede, 2006) and such games have been recently developed to educate and inform audiences on a startlingly diverse range of issues including, but not limited to, climate change policy (Castronova and Knowles, 2015), infrastructure management (Mayer and Bekebrede, 2006), Alzheimer’s care provision (Arambarri et al., 2014), and the promotion of cross-cultural awareness (Nyman Gomez and Berg Marklund, 2018).

Games can be a valuable tool in explaining complex systems and phenomena that are hard to explain through standard means (Castronova and Knowles, 2015). In relation to the broad scope of work in criminology, we have seen the recent development of serious board games that seek to do a number of things including explaining the asylum process (Right to Remain, 2020), supporting those in recovery from substance use disorder (Inspirado Hubs, 2018), demystifying arranged marriage (Sayej, 2017), and facilitating conversations between people in prison and their children (Lloyd-Jones, 2019).

The familiar form of a board game enables us to engage audiences in a collaborative act of play that opens new spaces for conversation. Through Probationary we sought to explore the potential of gameplay to open conversations that could inform changes to both policy and practice. With PTown Bay MMXXX, we are seeking to build upon this, harnessing the power of games as a focal point of artistic production with young people, and employing gaming as a way of developing our approach to engaging audiences. By taking players on a journey, we believe that games of this type can be a valuable campaigning tool.

PTown Bay MMXXX – play as a means of engagement

Set in 2030 (MMXXX), petrol and diesel car sales have been banned and the Peterborough landscape navigated by players has been drastically changed by climate change and sea level rises. Players of PTown Bay MMXXX must navigate their way around the newly coastal city completing missions, meeting local characters, and collaborating and competing with other players. Taking the player on a journey through the experiences of young people, the game seeks to facilitate an understanding of the world from their perspective, not simply by hearing about it, but through a visceral experience that play is uniquely placed to induce.

This is not a ‘Peterborough Monopoly’, instead the locations, missions, characters, and map are influenced by the young people’s view of the city they live in. The game was developed through twenty-seven workshop sessions conducted over two years at the Nacro centre in Peterborough. The first phase of workshops in 2021 involved five young men of school age attending the Nacro education centre and the second phase in 2022, involved three young people aged 16 to 18 on vocational studies programmes. Nacro centres are open to anyone, but the small class sizes, tailored approach and additional personal support often appeal to those who have experienced a broken or interrupted academic career. Young people accessing education or training through Nacro have typically faced disadvantage, nearly half have an identified learning disability and 70% access either the bursary or are eligible for free school meals (Nacro 2022). The sessions run with the young people involved in this project involved playing games, talking cars, going on fantasy drives, debating local landmarks, and sketching out future dreams.

Part of the challenge for the artists was to bring the young people into a discussion about the environment in a way that was meaningful to them. In response, the first phase of workshops were steered initially by the young men’s interest in cars as a way into thinking about environmental issues. While it may appear counterintuitive to approach the issue of climate change through an appreciation of the car, the format of the workshops enabled the artists to utilise this as an entry point for the young people to be able to think about the future. By focussing on the ban on the sale of new petrol and diesel cars in the UK from 2030, the future of the car became a way of thinking about the future in much broader terms. This opened discussion about future aspirations and expectations as well as the possible impacts of environmental change on the futures imagined by the participants.

As Hwa Young Jung has explained: “This project provides a different lens on the climate change debate. The lived experiences of the young people who developed this game with me really highlighted how the big existential issues relating to the climate change barely scratched the surface with them. Not because they were disinterested but the challenges of their daily lives, the immediate environment and the people in their communities felt more urgent”.

The workshops demonstrated that the dominant reference points in key debates, including those about both the climate emergency and broader environmental issues, are not always sufficient to capture the attention and interest of young people. For some, the urgency and importance of environmental issues need to be highlighted and addressed differently, and the methodology employed here enabled the workshops to evolve in line with the interests and concerns of the participants. In line with the central principles of socially engaged arts practice, the young people assumed a role as co-producers of the game, shaping its form and focus under the guidance of Hwa Young Jung.

Both the production process and the playing of the game seek to allow young people to explore how their engagement with the environment and nature can impact on their futures in a micro and macro context. Environmental and social factors, including the climate crisis, are presented as some of the many issues the young people face, as we work together to explore their understanding of where they belong in the world. By creating a framework to examine our everyday surroundings, we expand our conception of how living things are interconnected, to dream bigger and find alternatives to the ways things are now.

The game making ‘task’ opened conversations on two main fronts. In the first instance, the young people explored the impact of environmental factors – contemporary and future – on their lifestyles, engagement in civil society, their relationship with social institutions, experience of the criminal justice system and their life chances. Secondly, by thinking about the potential transformation of their home city in a future affected by climate change, the young people were able to think about questions of community, belonging, integration and exclusion. The game, and the map that organises it, stands as a representation of the young people’s view of the world, their future, and their place in their local community.

The car became the vehicle through which the young people were willing and able to examine the issues of environment and community. It was through an exploration of the future form, role, and status of the car that the young people were able to consider the challenges of climate change and to think about their future. Approaching their home city in and through the car, also enabled the young people to explore their relationship to, and place in, their community. As players, we become the driver, navigating a future Peterborough through the eyes of marginalised young people.

As a result, the game provides a way for us to understand the current and near future aspirations of young people faced with multiple disadvantages. It also asks us to think about the ways in which marginalised young people can inform debates about the future of their environment and their community. Approaching complex systems and institutions through the lens of art in this way means that players can enter a different reality. PTown Bay MMXXX asks us to navigate through a series of different narratives, experiences, and emotions to begin to better understand, or to perhaps think differently about, the experiences of young people and their place in debates about our shared future.

Social inclusion and stemming the flow

PTown Bay MMXXX deals with issues that are of both great significance and urgency but does so in a way that is accessible to a wide range of audiences. The production of an artwork of this type and in this way, provides us with a space to examine the experiences and aspirations of marginalised young people unavailable to standard research methods. To explore and then present experiences in an artistic form, and moreover in a game that can, and must, be played to be appreciated, opens our research and campaigning to new audiences. The attempt to understand the views, experiences, and aspirations of marginalised young people is vital if we seek shared solutions to shared problems. We must recognise the connections between community and environment as we plan for ‘our’ future; we cannot expect a truly collective effort to tackle environmental threats if there are groups who do not feel part of the communities we seek to protect.

As Hwa Young Jung explains, PTown Bay MMXXX is “a board game interpretation of an open world video game, in a prophetic vision of Peterborough, based on what’s important to the young people now”. Highlighting the key features of life in PTown, the game reveals the young people’s view of their community and their place within it. The landmarks and features included in – as well as those omitted from – PTown provide us with a view of what is important to these young people.

We are confronted with a Peterborough marked by the places and institutions that register in the everyday lives of the young people who created it and those that they foresee being significant in this imagined future. In navigating our way between the distribution centre, the Chicken Palace, and the police station we learn more about the reference points in the community experienced and valued by these young people.

As we look to address our collective future in the face of the climate emergency, this game asks us to address the very different experiences, values and sense of belonging that can define life for different groups within the same community. As we seek to address multiple challenges in the search for social, climate and criminal justice, we must look to the margins to develop a genuinely collective response.

To engage young people in this way brings personal and social benefits. Artistic production of this type contributes to capacity building among participants, particularly for those outside of core institutions and on the margins of our communities. Bonds with family and school, alongside efforts at increasing social inclusion, can be key to reducing risks of criminalisation (Smith 2006). Criminological research has highlighted the importance of community (re)integration and fostering a sense of belonging as key dynamics in efforts to prevent crime (Sutton et al 2021) and support desistance from offending (Graham and McNeill, 2017).

For young people in particular, research suggests that those who have fallen out of, or been excluded from, mainstream education are at much greater risk of criminal justice involvement (Holden and Lloyd, 2004; McAra and McVie, 2010; Sanders, Liebenberg and Munford 2018; de Friend, 2019). Alongside the personal benefits to reducing this risk, there are also broad social benefits to communities on a local and national scale of stemming the flow of young people into the criminal justice system (Bateman 2020).

We need innovative strategies to bring young people into debates about the future – in both social and environmental terms – and innovative means of hearing and sharing their contributions. To approach the environment through an appreciation of the car may seem counter-intuitive, but if this is the vehicle through which the future becomes imaginable, and debates become relevant, then it is an important way in. This rap, written by one of the participants, demonstrate that the production of a game in this way has the potential to transform ambivalence into engagement. To ‘play at’ serious issues like climate change and social exclusion also may seem to trivialise them, but this is not the case in a game like this. To game, and to play, in this way is to take seriously the participants involved, the experiences they share, and the views they express.

It is our view that Criminological Artivism provides us with a new and effective way of engaging audiences with a view to informing campaigns for penal reform as well as social and climate justice as PTown Bay MMXXX demonstrates. Our plan now is to explore the potential of PTown Bay MMXXX by sharing it with audiences. This began with gameplay events organised to coincide with the Cop26 Climate Change conference in Glasgow in November 2021 and a live streamed game during the Science Gallery International Youth Symposium in July 2022. We will continue as we share the game to provide opinion formers and policy makers with a different perspective to inform the development of environmental and social policies.

Acknowledgments

- The young people who created this game: Dans, Emilijas, Kye, Oscar, Riley, Andy, Nagina, Natalie

- The co-facilitators Prin Marshall and Hana Sayeed

- The staff at the Nacro education centre Peterborough

References

- Bateman, T (2020) The state of youth justice 2020: an overview of trends and developments. National Association for Youth Justice. Available at: https://thenayj.org.uk/cmsAdmin/uploads/state-of-youth-justice-2020-final-sep20.pdf (accessed 18th May 2022)

- Castronova, E, Knowles, I (2015) Modding board games into serious games: the case of climate policy. International Journal of Serious Games 2(3): 41–62

- de Friend, R (2019) Challenging School Exclusions: A Report by JUSTICE. Available at: https://staging.justice.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2020/08/Challenging-Report.pdf (accessed 25th April 2022)

- Holden, T and Lloyd, R (2004) The role of education in enhancing life chances and preventing offending: Home Office Development and Practice Report. Available at https://dera.ioe.ac.uk/8465/1/dpr19.pdf (accessed 27th April 2022)

- Inspirado Hubs (2018) Welcome to Inspirado Hubs. Available at: https://www.inspiradohubs.co.uk/?lightbox=dataItem-jd9aqr6d1 (accessed 26th April 2022)

- Jackson W, Murray E, Hayes A. (2020) ‘Playing the Game? A criminological account of the making and sharing of Probationary: The Game of Life on Licence’, Probation Journal: the journal of community and criminal justice, 67: 375-392

- Lloyd-Jones T (2019) One year on: unblocking conversations in prison, Central St Martins. Available at: https://www.arts.ac.uk/colleges/central-saint-martins/stories/unblocking-conversations-in-prison (accessed 12th April 2022).

- Mayer, I, Bekebrede, G (2006) Serious games and ‘simulation based e-learning’ for infrastructure management. In: Pivec, M (ed.), The Future of Learning. Affective and Emotional Aspects of Human-Computer Interaction. Amsterdam: IOS Press, pp.136–151.

- McAra, L and McVie, S (2010) Youth crime and justice: Key messages from the Edinburgh Study of Youth Transitions and Crime, Criminology & Criminal Justice. 10(2) 179–209

- Graham, H and McNeill, F (2017) ‘Desistance: envisioning futures’. In: Carlen, P and Ayres Franca, L (eds) Alternative Criminologies. London: Routledge.

- Murray, ET, Davies, K, Gee, E (2019) ‘The Separate System? A Conversation on Collaborative Artisic Practice with Veterans-in-Prison’. In: Lippens, R, Murray, E (eds), Representing the Experience of War and Atrocity: Interdisciplinary Explorations in Visual Criminology. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Nacro (2022) Education. Available at: https://www.nacro.org.uk/education/ (accessed 2nd August 2022)

- Nyman Gomez, C, Berg Marklund, B (2018) A game-based tool for cross-cultural discussion: encouraging cultural awareness with board games. International Journal of Serious Games 5(1): 81–97.

- Right to Remain (2020) Asylum Navigation Board. Available at: https://righttoremain.org.uk/shop/product/asylum-navigation-board/ (accessed 21 March 2022).

- Sanders, J., Liebenberg, L., and Munford, R (2018) ‘The impact of school exclusion on later justice system involvement: investigating the experiences of male and female students’, Educational Review, 72(3): 386-403

- Sayej, N (2017) ‘Darkness masked in lightness’: the designer using a board game to avoid arranged marriage. The Guardian, 8 August. Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/2017/aug/08/nashra-balagamwala-pakistan-arranged-marriage-board-gamearranged-marriage-board-game-nashra-balagamwala-pakistan (accessed 20 March 2022).

- Smith, D.J. (2006) Social Inclusion and Early Desistance from Crime. Edinburgh Study of Youth Transitions and Crime, Research Digest No. 12. Edinburgh: Centre for Law and Society

- Sutton, A., Cherney, A., White, R., and Garner, C (2021) Crime Prevention: Principles, Perspectives and Practices, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Tate (2021) Socially Engaged Practice. Available at: https://www.tate.org.uk/art/art-terms/s/socially-engaged-practice (accessed 26th April 2022).